When you were a kid, I’m sure this happened to you at least once: you were lost in a crowd, small and bewildered in a sea of giants. Suddenly, you saw your dad—relieved, you jogged to catch up to him and squeezed his hand. But when he turned around, a stranger’s face stared down at you instead. You spent a few seconds drenched in freezing panic before your real father ran over and hurried you away. You forgot about the stranger and that half-second of terror almost instantly.

Most kids forget, just like they forget the other minor horrors that make up childhood—the barking dogs, trips to the dentist, bikes crashing into bushes. I wish I could forget, and I wish that what happened to me when I was a kid was just a stupid thing I could laugh about. My girlfriend Sarah would tell me to not even write this, to let what’s in the past stay in the past. But I need to get this all down. I need to remember.

I was six. I was spending the weekend with my dad at Coney Island. We had just gotten off the tilt-a-whirl—head spinning, I wandered through masses of tourists, dazed by the bright sunlight and the suffocating smells of frying grease and powdered sugar. I thought my dad was right beside me, but when I looked over, he was gone. His slicked-back blond hair and salmon-colored shirt bobbed maybe ten feet away from me. I darted through the crowd and tugged on the leg of his khakis.

The man I thought was my dad turned his head and I saw…I’ve tried to explain what I saw a thousand times, to a dozen shrinks and therapists, and they all gave me the same blank, detached look. Like I’m crazy. At first, the face that looked back at me WAS my dad. The same rough, pockmarked construction worker’s skin, the same crooked nose, the same blue eyes. He knelt down so his face was level with my own and smiled. That smile was how I knew something was wrong, even before this skin started to soften and sag, even before his chin began to drip like melting candle wax. It was a hungry, mindless, animal smile, a drooling hyena smile, and even before his skull started to collapse and distend like rotting fruit, I screamed. I screamed and screamed, kept screaming even when I felt muscular arms wrap around my waist and carry me up over the crowd. I kept screaming because I could still see that melting, running, sagging face smiling at me in the sea of strangers. I kept screaming when the thing in the crowd winked at me as its ears slid down the sides of its neck.

My dad—my real dad, the one who rescued me—sat me down at a bench behind an ice cream stand and tried to get me to stop sobbing. I kept babbling about a monster. He held me against his burly shoulder and told me I had just imagined it, that there was no such thing as monsters. He bought me a strawberry sundae, but I kept crying and we had to go back to our little suburban tract house early. After my tears faded, I fell into a silence that scared my dad and especially my mom, a big-time worrier who hadn’t wanted us to go to Coney Island in the first place because she thought I would fall out of the Ferris wheel and break my neck. I was a talkative, active, goofy kid, but here I was skipping dinner and going to bed before sundown. I stayed in bed for the next few days, wide awake, staring at the ceiling, not moving even though I heard my parents whispering and arguing downstairs. When I closed my eyes, all I could see was that melting face.

My dad gave me a stern talking-to that night, told me I was frightening my mother and I needed to get back to school. I loved my dad and hated the idea of getting in trouble with my mom, so I obeyed. Even in the colorful, brightly-lit halls of my elementary school, even in the safe kindergarten classroom with its paper flowers on the walls, the nightmare wasn’t over. During playtime, I watched my classmate Melissa’s cheeks sag off of her skull and her tongue dribble down the front of her dress as she brushed her doll’s hair. Her green eyes were fixed on me the entire time, even when her jaw drooped off one of its hinges, even when her pigtails began to slide off. But even when I shrieked and pointed, no one saw what I saw, and when I looked again, Melissa was back to normal. In the school nurse’s office, friendly Nurse Fran smiled that empty, hungry hyena smile as she took my temperature. I watched her earlobes melt and her belly slide out from under her scrubs and sag towards the floor.

When I told my mom everything I’d seen—I was too young then to realize I should have lied—she sent me to a different kind of doctor. My memories of childhood are marked by beige therapist’s offices filled with toys I wasn’t allowed to play with, men in sweaters and rimless glasses asking to describe my feelings using colors, orange bottles of pills that made my head feel like it was stuffed with wet socks. I remember a white-haired lady therapist asking me to draw a picture of the melting people. I scribbled in their faces with crayon and then smeared the thick layer of wax with my thumb. The doctor stared at that picture for a long time and then put it into a folder. Later I saw my mom sitting at the kitchen table with all the lights off, gazing down at my drawing, her hand over her mouth, tears rolling silently down her face.

Sometimes the doctor’s faces melted—sometimes a lot, skulls sagging inwards like old pumpkins, and sometimes just a little, one ear dripping down a little further than the other, like they were teasing me. From the questions they asked, the doctors seemed to think that I thought everyone I knew was secretly a monster all the time and I was the only human. But I knew my dad was really my dad, that he loved me and made me pancakes shaped like animals, I knew Melissa was just a normal little girl who picked her nose when she thought no one was looking, I knew Nurse Fran was just a regular friendly nurse who gave you pink pills if you had a stomachache. The melting people were just borrowing the faces of the people I knew. At least, that’s what I had to tell myself in order to sleep at night and not spend every waking moment screaming.

The melting people were horrifying, but they never actually hurt me. They just grinned and stared at me with their idiotic, empty, hungry eyes. So I started ignoring them. I learned to swallow my screams, to close my eyes when I saw the schoolbus driver’s neck leak over his uniform collar. When I opened my eyes, the melting people went back to normal. Usually. I was sick of taking the pills that made my skull feel heavy and stuffy, so I told the doctor I stopped seeing the melting people, even as I watched his nose soften and slide down his chin.

After a while, I really did stop seeing the horrible faces as often. Sure, every once in a while, I would catch one of them looking at me, but always from a distance—a kid with his arms dripping out of his sleeves at a baseball game, a woman at the supermarket with one eyeball dripping down her cheek. But these sightings grew less and less frequent, and after a few years, they stopped completely. I grew up, went on to high school, did well on the track team, won a scholarship. My dad died of a heart attack when I was seventeen. I hated leaving my mom behind—she was so fragile, especially since dad passed, and she worried about me so much—but I headed off to New England to go to college.

That’s where I met Sarah, a pretty sociology major who loved wearing bright colors, singing along to classic rock in her car, and—amazingly—me. She thought I was quiet because I was shy. She didn’t know about the years of therapist’s offices and nightmares. With her, I could just be myself. Little by little, I forgot about being the crazy kid. I got caught up in an awesomely normal world of studying for exams, working at a coffee shop, going on hikes with my girlfriend, staying up late playing video games.

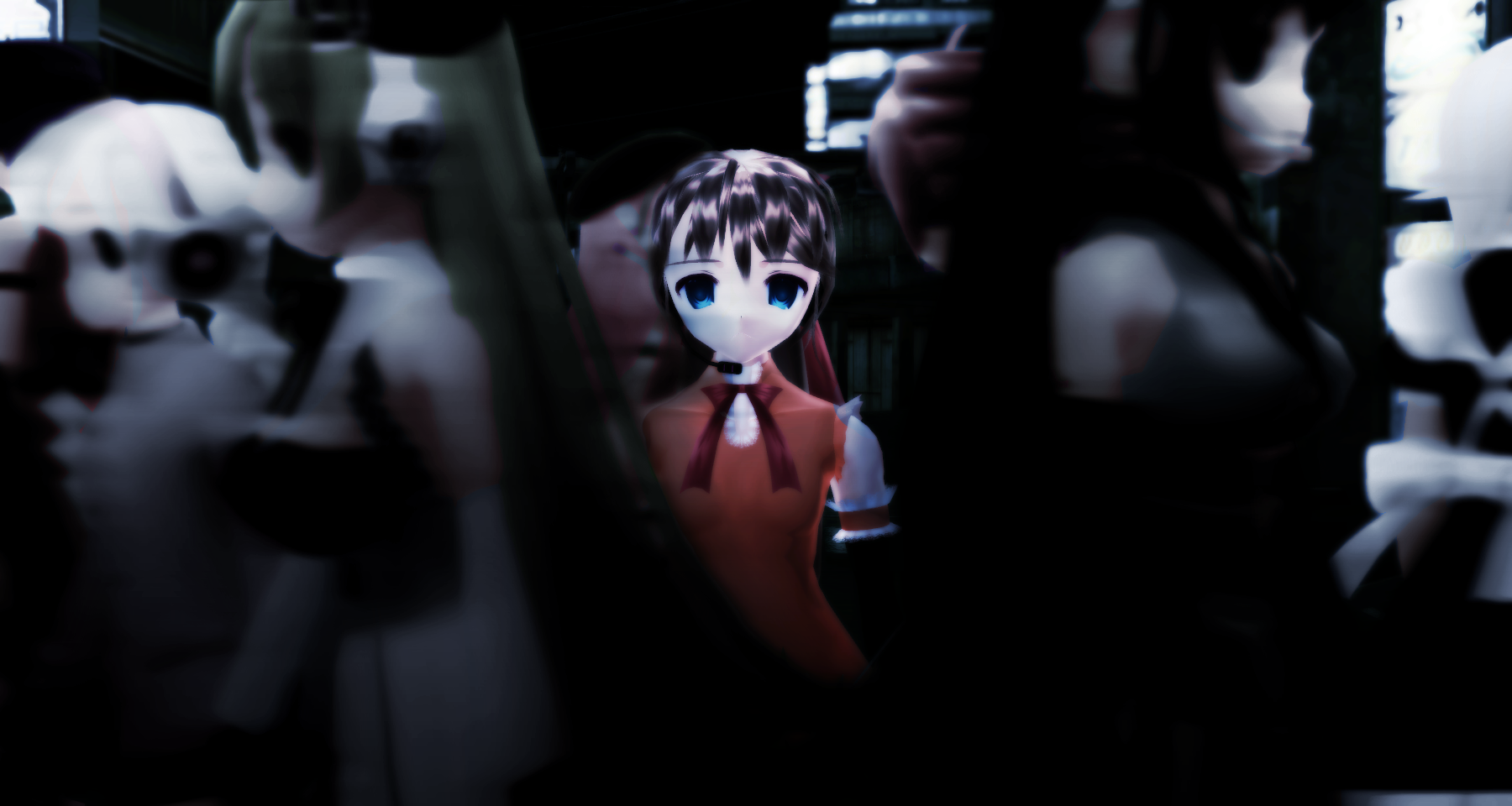

Just past three AM. Sarah was already in bed and I was downstairs playing TF2 in my boxers. My eyes started to go blurry. I got up, stumbled up the narrow steps to the bedroom. I saw Sarah draped in a blanket, face hidden by a pillow, her bare shoulder rising and falling softly as she slept. She looked so pretty and peaceful when she was dreaming. I climbed carefully into bed and silently kissed her shoulderblade, pulling her body close against mine. With my fingertips, I brushed her dark hair back from her forehead.

My fingers sank into her head like it was a rotting gourd. She rolled over—I felt the gummy matter of her skull clinging to my hand like wet dough—and she looked at me. She smiled.

I’m crouched in the corner now, facing the wall, trying not to breathe too loudly. I know when I turn around, my girlfriend will be sleeping in our bed, whole and normal and beautiful. I know this. I know this. I know this even as I see that wide empty grin reflected in my laptop screen. Even as I watch the face around it dissolve.

—

Credits to: photofreecreepypasta

Comments