From the personal diary of Annabel McGregor:

“7 January, 1932

Garris came home today. He seemed paler than he used to… much more quiet. I wish there was something I could do… I wish I could bring him back to us. But he’s gone. I have to accept that. We all have to.”

As it turns out, the diary of Annabel McGregor (Garris Creely’s adoptive mother, for those of you who don’t remember.) was used in the writing of a 1998 psychological thesis by Catherine Jacobs entitled; “From Garris to Hannah: A Study as to the Affects of Child Molestation.” In this book, the author uses materials from various different child molestation trials to form an in-depth study on the resulting mental scars such experiences can produce in children. Annabel’s entries themselves aren’t that relevant, often repeating the same things over and over, but they do form a cohesive thread between two big events in Garris Creely’s life: his release from the West Riding Mental Hospital, and his journey back to America.

According to Annabel McGregor, nineteen-year-old Garris Creely left his parents a week after returning to them, going off to work in a shoe factory. After being fired for inability to follow proper safety instruction, he worked as an assistant ballet instructor in London. Six weeks after this, he returned to his parents, where he learned that they had been harboring a secret from him.

After Sheridan, his previous adoptive father, had died, Garris was left to inherit all of his belongings… this included the expansive novel "Puppets," and the script and score for Puppetmaster, the musical version of the same novel.

From the personal diary of Annabel McGregor:

“18 September, 1932

Garris called to tell us he was leaving. We asked when he was coming

home. He hung up after that. It’s been four days, and I’m beginning to

believe that I won’t see him ever again.”

Not much is known about Garris Creely after that. The next existing record of him is in a financial statement in 1933, concerning an inquiry for a choreographer for "The Puppetmaster’s Regime."

It would appear that Garris was continuing his adoptive father’s work.

Why on earth Garris Creely would drop everything in his life to continue the work of his childhood rapist is beyond all logical comprehension. One reason could be that he wanted to understand his father more… he was, after all, Sheridan’s son. Perhaps he understood how much Puppetmaster had meant to him, and had devoted himself to polishing up the production. In Catherine Jacobs’s book, she details a great many examples of this.

In the letter from Garris to the aforementioned choreographer, he writes, “I hope to enliven the production with a bit of playful mystery--such as the essence of the original novel format.”

I don’t have the complete manuscript for "Puppets," though Catherine Jacobs apparently does own a small snippet of about 200 pages (god only knows how she acquired this). She lists a total of seventeen excerpts in her book.

From what I’ve read, the prose of Puppets is very difficult to comprehend. One might assume that Sheridan hadn’t ever stopped writing it, and had never revised. The story itself follows the main character; Morietur Abinces, as he goes off on an adventure to explore his own sexual agenda upon the request of a puppet that he meets in a dream. To get a feel for the odd, flowery nature of the writing, here’s an excerpt:

“The puppet was as black as night upon the cold winter eves of Lammastide…light and airy, yet weak and bitterly sharp. Upon sensing the figure’s wooden presence, he scattered himself about the room, unable to find a proper door or window to relieve his urge to escape the angry monstrosity. His eyes danced along the riverway of contempt, stealing glances of the form that beckoned for him to remain motionless. Defeated, he rested himself within his own terror, bending as he slipped into his remorse and fear.”

I have nothing to work on but the vague points provided by Miss Jacobs for this assumption, but I gather that Garris used his inheritance to fund the production of The Puppetmaster’s Regime. In the box “34 Creely-Wright”, I’ve found a small folder full of production notes from Garris that I had glossed over in my previous search. Nothing of great importance stands out, other than the pitch Creely used to gain attraction of several theater owners who were interested in housing the production. In this, Garris describes the show as “Upbeat, fraught with flowery production numbers and a moral all ages can relate to.”

I feel like this is a good time to bring up my meeting with Miss Alice Corley-James. I made sure to phone her grandchildren for permission to visit, for which I was declined three times. After I sent the cake, they understood my persistence, and I was granted access.

It was a six hour drive to the home of Alice Corley-James. Her granddaughter was hospitable enough--well, as hospitable as someone can be when they obviously don’t want you in their house. She took me to the living room and offered me some cake, which I declined. A few minutes later, I met Alice, who limped her way onto the couch with a plate of cake in hand. I tried speaking with her, but she refused to talk to me until she had finished eating. I took an instant liking to the old bat, nutty as she was.

Throughout the following Q&A, Alice made it very apparent that she had reviewed her facts. They seemed rehearsed and tired coming from her lips, but I didn’t think much of it.

From the Testament of Alice Corley-James (1926-Present)

Q: How old were you when you saw The Puppetmaster’s Regime?

A: Nine. I had just turned nine that Wednesday, and we were going to have a party the following Saturday.

Q: What do you remember about the production?

A: I don’t truly remember a lot about the show. I was young, I was hyperactive, and I was bored. Bored to tears by the entire thing. It was so very monotonous, and so blandly staged. I recall watching the three kiddies dancing the exact same motion - twist, tap, twist, tap - for almost four minutes, all while the ensemble walked in crisp lines. It was so awkward. That little boy playing the main character - Mory something-or-other - was a bit quiet if you asked me. He sort of mumble-spoke, squinting the entire show. Those vague, squinty eyes were bland too. I fell asleep halfway through Act I.

Q: And do you remember the end to Act I?

A: No. When I woke up, my parents were dragging me out of the theater. I spent the next three hours waiting by the street with my mother while my father searched for his brother - Uncle Devin was the assistant choreographer, you see. He died backstage… I think a lift collapsed. I don’t know. It was only when I was thirty did they actually tell me what happened…though I remember that they never acted the same again.

Q: Did your uncle keep any documentation of his time working on the production?

A: I wouldn’t know. We weren’t all that close to him, you see.

Q: If he did, where could I find those documents?

A: Either they’re still at the theater, or my father… oh, yes. My father probably had them. I remember the policemen delivering the box to us. Your best chance of finding it would be in the attic. We moved all of my father’s old office documents into a red… yes, it was red… a red chest. If it isn’t there, it was most likely thrown away.

Mrs. James’s granddaughter aided me in my search, and together we found the red chest - as well as Devin Corley’s belongings. They had been shoved into a small storage crate within the chest, sloppily strewn in wrinkled chunks of paper. I offered Alice the opportunity to rifle through the crate, but she politely shooed me out of her house before asking for another piece of cake.

At first, I couldn’t make much sense of the contents within the box. There are a few bills, some blasé production notes, and a list of ensemble performers. However, one particular sheet of paper did catch my interest - the audition notes for the role of Morietur. For those of you who don’t remember, this was the character whose actor was last seen begging the audience to help him on the night of Puppetmaster’s premiere.

Not many names are found in this file, oddly enough, just fourteen boys and six girls. Underneath the various names are notes over the auditions - notes such as “Too cheeky,” “Too quiet,” “Too mumble-mouthed” …but about three-fourths into the paper, the name “Timmy Wright” is circled three times, a small star etched beside it.

“He’s the one,” the note reads, boldly.

I’ve done a bit of research on this performer, as well:

Timothy Cartwright was born on August 16, 1923. His father, Vincent Cartwright, was a lighting designer for a theater on Broadway at the time. His wife, Margie, was a costume designer. Though little is known about the beginning of Timothy’s career, but by the age of nine he had taken the vaudeville world by storm as Timmy “cutie-pie” Wright, or “Cutie Wright” for short. As far as I can gather, his only Broadway credit before The Puppetmaster’s Regime was in a semi-successful flop called Joyful Hooligans, in which he played a young British boy who falls off of a ship and is taken in by a band of American teenage pickpockets.

Devin Corley’s diary details the arrival of Timmy to the theater. He says that Timmy was asked to be dropped off in the lobby without his parents. Garris Creely instructed the staff not to enter the lobby for an hour. At the end of this hour, Garris Creely himself came through the lobby doors, and found Timmy still in his seat by the receptionist desk. He was quoted to have looked “confused and scared, with a look in his eyes that likened to an old cat, weak and defenseless.” Garris lead him back to his office, where he waited for his parents to return to sign the proper paperwork.

The next few entries of Devin Corley’s diary describe the hiring of the rest of the cast and crew. Shirley Taxum was signed on to play Trahunt for three weeks, died in an automobile accident and was replaced by Sally Wilkes. Henry Gregory, another vaudeville performer who had worked with Timmy at least twice before, was signed on to play Adolebit. Other cast members included Fernando Peron as Mr. Obiscer, and Grace Day as Madame Reperio. The casting for the man in black, as well as The Puppet Dressed In Black, are not listed. Set design was done by Abraham Duarte, and costumes were done by Juliana White. Lighting and direction was taken up by Garris Creely himself.

For the first two weeks of production, Devin Corley’s description of Creely doesn’t seem too interesting. A bit eccentric, and a bit of a perfectionist…but he’s also described as “jolly and surreal, like the Santa impersonators you see at the department stores.” He was always cracking jokes, and, for the most part, had a good attitude. However, as innocent as his behavior seems, even from the beginning he has a strange obsession with Timothy Wright. Corley details an instance where Timmy was clearly getting the choreography wrong, and yet Garris berates the other children for messing him up. From Devin Corley’s perspective, he coddles the boy and barely even directs him.

Now, as lighthearted as he was, Garris Creely was also a rather strict director. Devin Corley claims that each of the cast members was to arrive at four in the morning - two hours before crew arrived - simply for vocal exercises and warm-ups. One entry states, “The ensemble was placed into three lines, and the children were lined up in front. Mr. Creely would spend fifteen minutes going over the exact same tap routine each morning. He always had Timmy do it first, and then the others were to follow. Afterwards, everyone was to gather in a circle for vocal warm-ups. It would start by going through their ranges, then Garris had us do that awful dance. There were to be two circles--one inside the other--and the cast would hold hands. Then, both circles were to dance around in opposite directions. The outer circle began the chant first, crying out “Seementael! Seementael!,” while the inner circle yelled out “Fraela! Fraela!.” Both chants were ensemble lyrics that had been cut from the production, but Mr. Creely saw fit to include them every morning, saying they were perfect vocal exercises.

Garris’s impatience continues throughout the rehearsals - he grows violent, and many cast members report to Devin that Sally Wilkes exhibited bruises on her upper arms. The script was modified weekly, putting the company in great stress. Timmy Wright was the one who took most of the damage, as most of the changes gave his character more lines, placing him under a lot of pressure. He was often asked to visit Creely’s office for private readings, where he’d stay for hours.

Tragedy entered the life of Timothy Cartwright on August 13th, 1933, when he and his family had been the victims of an automobile accident which killed his father, and severely injured both he and his mother. Devin writes that for a month and a half, Garris visited Timmy daily, and eventually stopped coming to rehearsals altogether. The principal choreographer, Mandus Thorman, took up the role of director during that time. It was also during this time that they sought out the employment of fourteen-year-old Rory Atkins to be the understudy for Timmy. Devin writes that it was at the conspiring of Thorman and the producers that Rory would eventually replace Timmy.

“This “Cutie Wright”,” writes one producer, “is completely inept in the art of performance. His delivery is too big, his eyes are too big, his presence is too big… and for all that bigness, he has a shocking little amount of talent and discipline. Mr. Creely spoils the boy, and hardly gives a scrap of motivational honesty in the direction of anyone else. In short, Timothy Cartwright must go.”

While Garris was gone, the production staff also persisted in cutting certain things from the show. This included a number that occurred midway through Act II. A gibberish number sang by an army of puppets, that they said “slowed down the production.” Creely was quite unhappy with this, giving them several angry phone calls about the matter. They eventually gave him an ultimatum: cut the number completely, or put it somewhere else. Garris placed it at the end of Act I. Devin notes that Garris would tell the children to practice this number on their own time, and when they did run through it during rehearsals, it was in segments, never in its entirety.

The number itself contained one group of lyrics that was repeated over and over again. Garris made it painfully clear that the company was to sing these stanzas exactly one-hundred times before they could take up a break during intermission--even if the curtains closed before they were finished.

Devin’s journal ends with a relieve from the notes throughout. Instead, he explains an event that he himself was present for. I think it’s best to simply copy the section itself:

“Nobody was ever allowed in Mr. Creely’s office but Mr. Creely and Timmy. I assumed Mr. Creely would want to meet Rory, but he never asked for an audience with him. However, Mandus had instructed me to deliver three resignation letters to Mr. Creely’s desk, and I went to my task.

When I came in, the room was all musty and hot… like there wasn’t even air conditioning there. The windows were drawn, but my vision adapted fairly quickly.

I saw that, on the floor, was a worn mattress with plates and cups all around. I blinked in surprise. Rushing over to the bedding, I saw that it had definitely been in use for quite a while. I wondered, in astonishment, if Mr. Creely had been living in the theater. When I considered the idea, I did recall that he’d put all of his money into this show, and we never heard him ask us to send papers to his house…only to his office.

Along the far end of the room were a few piles of shirts and trousers. It was still very dark, so I didn’t focus on them too much. I went to set the papers down on the desk, when, against my better judgment, I had the urge to snoop around a bit. I looked over the top of the desk - nothing but pens and scrambled folders - then went right to the center drawer.

What was inside the drawer frightens me more now than it did when I saw them. Within the drawer was a gun (a bit eccentric, maybe, but I thought nothing of it), as well as a worn, hand-painted mask. Red in color, it was put into the shape of a doll’s face. A puppet’s. Beside the mask was a small journal. I opened it, and found the pages to be yellowed with age. The pages themselves concealed mad writings that were barely legible, but I could tell by the drawings that it was some sort of worshiper's guide…there were these charcoal sketches of a puppet…a giant puppet that controlled the world on strings protruding from its fingernails. Other pictures showed the puppet walking amongst common men, who could not see it. There was a drawing of a man raping a small girl, the puppet controlling his arms. There was a man stroking the bodies of his wife and children, a young girl being bought for the night by an older gentlemen, two twins being held down on their bed by some invisible force…all pictures in which the puppet stood by, grinning.

I placed the journal back into the drawer, but then I noticed the mask. The mask had the same face that the puppet had…an insane grin, wide eyes, puffy cheeks. It was only when I held it closer to my face did I notice it also shared the features of Timmy. The same mouth, the same nose, the same eyes. I shoved the mask back into the drawer and shut it quickly, my curiosity morphing into sickness. I backed away from the desk and hit the wall. Turning to my right, I felt my foot come into contact with the pile of clothes I saw earlier. My eyes had completely adjusted to the dark by now, and I could see that not all of the shirts and trousers were in Mr. Creely’s size. At least four of them were smaller… the clothes a young boy would wear.

I grabbed the papers off the desk and ran out. I delivered them into Mr. Creely’s hand that afternoon''.”

After that, there are seven blank pages in the journal of Devin Corley. There are no more entries.

At the bottom of this crate, however, was a newspaper dated October 3rd, 1935. The headline reads “FLOWER SHOP VANDAL STRIKES AGAIN”, and on the third page is a small section dedicated to the “disaster” that occurred at the August Wilson Theatre on October 1st. Oddly enough, the article doesn’t mention The Puppetmaster’s Regime by name more than once, but it focuses on the aftermath:

In an interview with Police Officer Jeremy Winthropp:

“We ain’t got no idea what could of happened. [We] got a call from a diner down the street, talking about some riot going down at the August Wilson. [We] came to find a bunch of theatergoers crying and begging for help. [They] just kept saying “They’re dead! They’re dead! They’re really dead!”. We went inside, but we didn’t find nothing."

You see, seventy-six attendants of that 1935 showing went missing, ninety-eight if you count the theatre company, whose bodies were never recovered from the stage, though many testified to have seen them die. Others claimed to have seen people collapsing in the aisles. When police investigated the theater, they saw that one of the lifts backstage had collapsed, but there were no traces of anyone there. The only body recovered was that of Garris Creely. He had been found in his office, a bullet in his head. Other than that, nothing, No blood, no struggles. Those ninety-eight people were never seen again.

After that, there’s nothing left in the crate but barely-visible photos of cast members and fabric samples for costumes. At this point, my investigation to The Puppetmaster’s Regime ended. Or, at least, the historical investigation.

Do you remember the revival of Puppetmaster I mentioned in my first entry? Well, the first preview performance will take place in Chicago on September 18, and I’ve already booked balcony seats. (Being a full-time investigator for an obscure pornographic musical doesn’t lend itself to much of an earning, you see.)

I will be attending this showing, where I will record the audio and take notes on the production. I’ll do a detailed run-through of the production the day after I see it.

Investigation will resume September 18.

***

UPDATE: September 20

Alright, I never got around to posting the previous investigation. I know, I know, it was irresponsible, but during my wait for Puppetmaster, I started actually paying attention to my college courses, and I never really had time to revise my first draft. So I suppose I’ll just have to post my findings in one long entry, as I have seen the revival of Puppetmaster.

The experience was… odd. It’s hard to remember the things that went wrong unless I run through the entire thing in my head. It’s easier to write about the first act in that way, I guess. I know that doesn’t really make sense when you put it to words… but it’s hard to explain.

But enough of my cryptic buildup - I arrived in Chicago last week, where I stayed with a couple of old highschool friends for a few days. We had fun catching up, but I never took my mind off of The Puppetmaster’s Regime.

The theater that housed the production was rather obscure, located a few miles out from the main city. None of the news articles I’ve read post-preview have mentioned the name of the theater, so I can only imagine they don’t want the publicity.

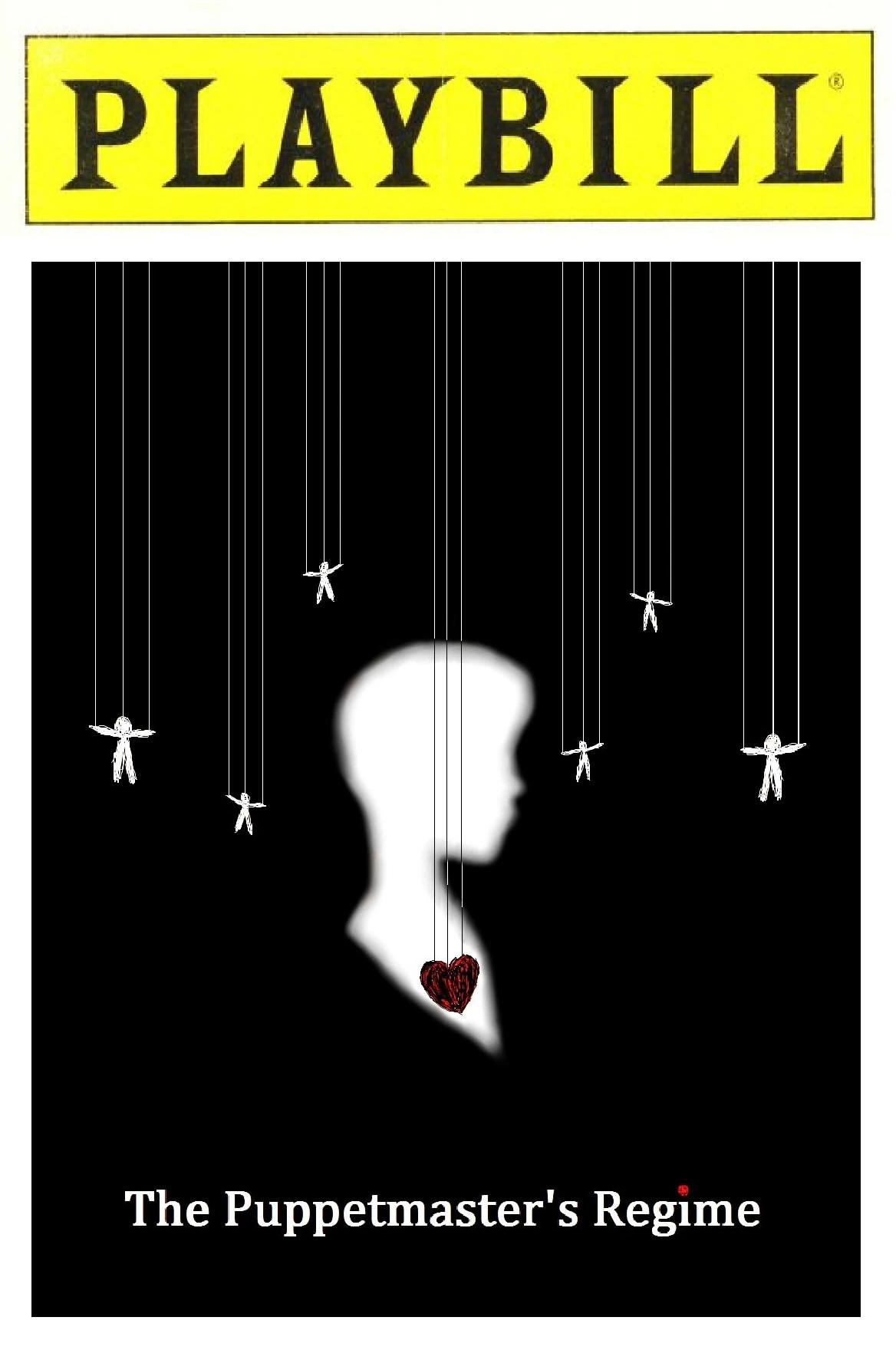

Upon entering the theatre, I was given a playbill by a cheery man in a suit - an older gentleman with a weak smile on his face. The playbill itself showed the white silhouette of a young boy, several puppet strings attached to a scribbly red-and-black heart that hung within his chest. There were white dollies hanging all around him. I remember thinking it was odd that a preview playbill would be in color, as those aren't usually printed until the show starts making money. Anyhow, I made it to my seat and began to read through the playbill itself. I didn’t care much about the names of the cast members, though I do recall seeing the picture for the boy playing the part of Morietur: a fourteen-year-old named Milton Holiday.

The show opened to a long, plodding overture - played mostly with piano, with these odd whistles being played through speakers all around the theater. After about five minutes, the music changed to a more bouncy, lighthearted tune, and the curtain came up.

The stage was empty, nothing but the projected backdrop of a village square, with these odd clouds floating above. About ten children in eighteenth-century German clothing skipped onstage, playing with balloons and dolls. As the music progressed, a small mechanical horse wheeled itself onstage. The lights dimmed, and the children stopped. The horse dragged along a cart, upon which a small curtained puppet box faced the audience. As the cart came to a stop, a large puppet in a black robe flew out from behind the curtain. The children screamed, and backed away.

Then the puppet spoke:

“Good day, little ones! What a wondrous day for bout of play, isn’t it? Now don’t you be frightened, sweetlings. The Puppet Dressed In Black has a tale to weave, and someone has to hear it. Why, even if a story isn’t terribly uplifting, it’s the relevance of the story that matters, isn’t it? Now gather, gather, my popinjays… for this story, I’m afraid, requires the keen ears of a curious child. For only the innocent can see things simply, without the distractions of growth.”

The children looked at each other, then slowly began to gather around the cart. Once they were all seated, the Puppet let out a chilling laugh.

“That’s the spirit, kiddies!” he sing-spoke. “Now, this is a story about many things…about love and hate, about dark and light…about the difference between right and wrong, and the difference between wrong and right. But, at the core, this is a story about a little boy named Morietur…”

And with that, the light on the cart fades away, and a light fades in on a small boy, holding a broom, smiling proudly. Morietur.

The rest of the prologue is rather bland, and I can’t remember (or decipher the audio to) much of the exposition. The Puppet, Morietur, and Mr. Obiscer share a song. We learn that Morietur was an orphan who Mr. Obiscer found on the side of the street five years ago, and has since put him to work in his puppet shop. The costumes from this point seem much less historically accurate from the opening scene. Everyone’s costumes seem faded and bland in color scheme, but each of the outfits are ridiculously frilly and layered. Some of the story’s exposition is changed. For example, Morietur’s last name; ‘Abinces’, had been reapplied from the novel on which the story was based.

The staging and set design is oddly reminiscent of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s The Woman In White…most of the sets are made up of hyper-realistic projections that give the illusion of a moving camera. However, unlike The Woman In White, there are far more set pieces which actually have moving images projected onto them - like the revival of "Sunday In The Park With George."

For example: During one of the opening songs; “I Can Hear Them Whisper,” we see Morietur sweep up around the puppet shop. We watch as the front desk and two puppet display shelves spin around on the turntable as the projected background spins slightly faster, adding in ominous shadows and subtle lighting changes. It was dizzying, but effective.

Most of Act I’s exposition seemed rather harmless in my opinion. It almost seems like the start of a Disney show. However, I did find my inner critic rolling his eyes at some of the puerile lyrics (my personal favorites being: “He pretended he was crying/though they told me he was lying,” and “He was a sickly boy/Knowing not of ‘joy’”.)

However, upon comparing the new version to what I’ve heard about of the other two; there are some significant changes to the show.

For example, The character of Madame Reperio has been cut completely. After the cutesy song “Get A Puppet”, we are taken to the center of the village. Here, we have one of the songs that had been cut in previous versions, entitled “Whitteltine,” in which the villagers celebrate a holiday of the same name. This celebration focuses on villagers dancing around with puppets and dolls made out of random objects such as twigs, scraps of clothing, and cornstalks. The music is charming, like a folksong… although the lyrics don’t seem to make much sense:

“Dancing as we pither through the withering and woe-!

Evermore aligned along the ever-growing row-!

Eyes without a trace of tones or livelihood and so-!

Rise and rejoice for a Whitteltine song…!

And the willows will wander all Whitteltine long…!''”

Here, the song where the children sell dolls is used as a bridge in the “Whitteltine” sequence.

Another change is the rearranging of “The Wind and the Whisperings”, a song that a was originally played in Act II. In this new version, it is sung monotonously by a group black-clad people mourning the loss of a young girl, a rape victim. The sequence itself is so strange… around eight people walk onstage, four of them carrying a small open coffin. The lighting goes from yellow-orange to blue, and the chorus drones on for about eight minutes as they somewhat explain how this girl died:

“''The wind was her muse for play…

And she pranced along the river way…

She slipped along the sides of the weeping willow’s hairs-

And she danced along the river way with nary a remorse.

The whisperings from far away…

Calling out for her to stay…

She stayed there with the wind and the whisperings of yore-

And she danced with him until he saw fit to take her source.''”

Again, this uncomfortable ensemble song goes on for about eight minutes. From what I could assume, the little girl had been playing along the river when a man asked her to stay with him until nighttime, where he raped her and tried to drown her before a policeman stopped him right as the girl had perished.

Other than that, most of Act I seemed the same as the other versions. Given, there is a small bit where a girl with a puppet mysteriously appears and disappears while Morietur sweeps up the shop, and a random scene right before the finale in which Mr. Obiscer sings about the hardships of raising Morietur. (A song reworked from the same song Madame Reperio sang in 1934.)

The finale’s song itself, which so many people had claimed held some sort of “force” to it in the 1934 production didn’t seem all that powerful. Though this may be due to a rewrite: the 1934 version was said to be significantly longer than the 1928 workshop, at around twelve minutes of nonstop gibberish lyrics. This version has a reprise of “The Wind and the Whisperings”, followed by a few versus told through the odd language. The lyrics are, in fact, somewhat odd-sounding after two minutes of nonstop strobe-lighting, but I wasn’t that affected by it. There weren’t any deaths after the finale, at least…though intermission did last ten minutes more than it was supposed to, due to technical difficulties backstage.

Act II was where most of the changes seemed to be. It began with a light on Morietur being strung up on ropes like a puppet, his friends and Mr. Obiscer hanging on either side of him. A new song plays where all the songs from Act I are placed into a montage, while the Act I Finale music plays in the background. Just as the music shifts to the pounding “Whitteltine” music, Morietur awakens.

Remember when I mentioned that Act II was mostly made up of a bunch of songs played one after the other for no apparent reason? Most of that has been cut. The only two songs from that long, drawn-out sequence are “What Is This Place?”, and “Morietur’s Soliloquy” (which has been renamed to “Morietur Confronts the Puppet”, and has been changed to a duet sequence.) The lyrics have been improved, as well. Whereas the 1934 show had lyrics such as this:

“What is this place?

What are you aiming?

This isn’t well, sir-

Why are we gaming?

This isn’t a game!”

The improved lyrics are:

“What is this place?

Wait, am I dreaming?

This isn’t real, no…

Nor what it’s seeming…

It’s all a dream!”

Still a bit clunky, but at least they make sense now. The particular scenes I listed before involve a panicking Morietur confronting the Puppet Dressed in Black, who explains that Morietur’s soul once belonged to a child rapist, and that he died before the Puppet could punish him. This is where the set designs became a bit… odd. There were several floor-to-ceiling metal dollies that would constantly roll about onstage, as if to symbolize Morietur walking somewhere. The backdrop went red, and there were projections of puppets flinging the corpses of children along the walls. To say it was unsettling would be an understatement.

After this, the story progresses in a similar manner as the 1928 workshop, but with different twists. Morietur learns that the odd-looking man in black from the first act was the boy that Morietur raped in a past life. The man in black wants to revisit their relationship, but Morietur wants nothing to do with him. They spend the next ten minutes singing about what might have been, and Morietur begins to remember things. He ends up seducing and dominating the man in black, and they have sex on a bed while a group of children acrobats frolic about on long sheets of fabric above them.

Just then, the Puppet Dressed in Black shows up, and orders the old man to go away. He explains to Morietur that his punishment is to forever serve him, aiding in the future rape and murder of children in the village where he lives. As they both sing the title song, several children (including the little girl who drowned in Act I) join in, all holding miniature puppets dressed in black.

The new ending is a bit confusing, but apparently they’re saying that pedophilia is some sort of vicious cycle…when a pedophile dies, his soul is placed in that of a newborn child, who will, by fate, be raped themselves...this influences them to become child molesters in their adulthood. Morietur, as well as several other children, manage to defy destiny by escaping their respective rapists - which results in their being enlisted into "The Puppetmaster’s Regime." It makes so little sense, and it’s so damn creepy.

Then, just like in the 1928 workshop, all of Morietur’s friends are returned to the puppet shop… but none of them have any memory of Morietur.

We cut back to the cart from the prologue, where we see that all the children have disappeared. From the back of the puppet box, Morietur and the man in black exit from behind the curtains. They hop upon the horse, and begin to trot their way out of the town, As they exit the village, they hear a small girl’s terrified screams, and she lunges out in front of the cart. She begins to beg Morietur and the man to help her, just as an old man rushes out in pursuit. He insists he is the girl’s father, but she sobs that she’s never met him before. Panicked, Morietur pulls on the horse reins, and runs over the man, killing him. The man in black turns to Morietur and, his voice low, whispers, “Morietur, what have you done…?” before the lights go out.

However, right after this scene is where things quickly became… wrong. The lights slowly faded from the green tint of the forest into a deep blue, similar to the lighting during “The Wind and the Whisperings.” The entire company slips out from backstage holding their miniature puppets, staring directly at the audience.

Just then, the lights began to flash…and the puppets… I know this sounds kind of stupid to say… but they sang. I don’t mean that the children sang while controlling the puppet’s mouths - the puppets actually sang.

And oh god, the song.

It was that same gibberish from the Act I finale.

The children, the adults, all of them were holding puppets. They chanted those horrible words over and over again, their eyes unblinking, focused on the audience. Trapped in our seats, we were forced to listen to the song repeat itself over and over. I saw that the cast had begun to move the puppet’s around in jerking, near-erotic dance moves, every now and again twitching in unison with the rest of the company. After a while, I began to feel sick. We were all sick. I could see people in front of me leave their seats, ready to leave. I tried tuning the chants out, but that only seemed to make them worse. The music pounded within me, causing me to jerk about with each pounding drum. As I leached back in my seat, I realized something. The pounding within me wasn’t just from the orchestra… it was from beneath me. For a moment, I could see that everyone else could see it, too. For a faint moment, we could feel the ground beneath us quake along with the chants. I looked up to see if the cast had noticed, but then I saw the puppets. They were still dancing and moving within the performers’ grasps… but the performers themselves were not moving their arms.

And then, for a moment, we all found relief.

From backstage, several crew members rushed onto the stage, pushing several actors away in the process. One of them screamed out “Fire! Shit!” and then the chaos began.

From above the stage, all the lights began to shoot off. The projections behind the actors flickered briefly, before shutting off entirely. The company screamed, as did the audience. In a flash of fire and sparks, the actors began to leap off the stage, and we all began to pile out the door. I still had a headache. I could still hear the pounding.

The fire department arrived shortly after the theater was evacuated. About ten minutes before the trucks arrived, we heard the back of the theater collapse. I’ve since checked the articles online, and sixty-plus attendants of that show (nine of them being the cast and crew) have gone missing. As it turned out, most of the people who didn’t leave the parking lot were either helping out (like me), or were too shaken up to drive. When I finally began walking towards my car, a gurnee was wheeled right past me. The man I saw laying there, unconscious and hooked up to an oxygen tank, was the same man who had handed me the playbill.

I drove back to my friend’s apartment and went straight to bed. Even in my sleep, I could still hear the pounding.

By morning, my headache had stopped, but the memory of the night before still lingered. I went to my computer straight away to upload the audio I had recorded. My camera tends to divide long videos into smaller ones, and I immediately deleted the last video. Nobody ever needed to hear that…especially not me. I listened through the recording again, making notes in Word Processor as I went along. I found myself humming to some of the more bouncy tunes, the pounding slowly fading away. My fear of the show had lessened. The idea of supernatural forces destroying the theater seemed far too ridiculous for me to take seriously, and I bushed my fear aside.

Once that was done, I went to work scanning the playbill. After scanning the front, I went to work scanning the interior pages. A bit curious, I skimmed through some of the production names.

And it was then, right there on the third page, I saw the picture of the man who had handed me the playbill. The man was the Head Producer/Director, I learned. A cheery old man with a wrinkled face, looking away from the camera. Below his picture, in bold letters, read the name: Timothy Cartwright

My face scrunched. My breath went still. All I could hear was the faint memory of the pounding. That isn’t right, I told myself. It isn’t possible. It’s a different person. It had to be. Timmy Wright died on October 1st, 1935 at the premiere of The Puppetmaster’s Regime. Everyone saw it. Everyone saw him begging for help, strung up on strings - this isn’t possible.

Then I remembered something.

In my interview with Alice Corley-James, she mentioned Morietur’s “squinty eyes,” and his “monotonous acting.” Timmy Wright was known for his wide-eyed expressions and over-the-top delivery. It’s what made him famous. The person performing Morietur that night in 1934 must have been Rory Atkins, the understudy.

That, and Garris Creely had been found dead - killed by a gunshot to the head. Everyone assumed it was suicide. Nobody even suspected murder. I remembered Devin’s journal - the puppet mask, the clothes, the fascination Garris Creely had with little Cutie Wright. Nobody even suspected murder. Why would they?

And then, to add to my revelation, I realized that among the cast members who had escaped from the theater, there was one boy sitting in the backseat of his mother’s car… the vague, empty face of Milton Holiday. Morietur.

"The Puppetmaster’s Regime" is not a simple musical, I’ve come to realize. It’s more than just a production. It’s a force. An entity, even. It’s not just a madman’s sick, elaborate scheme to rape his own son… it isn’t just a young boy’s obsession over destroying his father’s work…it isn’t only an innocent victim’s last attempt at showing the world how he was wronged… it’s a greater monster than that. Within the writing and music of this show is something… I don’t know what, and I don’t want to know what. Some kind of monster that refuses to die. People who saw "The Puppetmaster’s Regime" in both 1928 and 1934 were said to have suffered from life-long mental affects, causing them to hum tunes they had heard only once.

Even now as I type, I quietly hum the sick, demented tune of “Never mind Me, Mister.” When I sleep, “The Wind and the Whisperings” refuses to rid itself from my subconscious. I find myself thinking about this production night and day, singing and thinking about possible depth to certain subplots and songs. What’s worse is that I know that someday another revival of the demented work will make it’s way onto the stage… Milton Holiday is still alive, isn’t he? And this evil won’t rest until it remakes itself again.

I’ve decided not to post anymore of my findings - this includes the audio taken of the revival. And I suggest that none of you attempt to look further into the matter. It simply isn’t worth it.

****

UPDATE: September 27

A few days after writing this I read a few articles about the fire at the theater. Those sixty-plus missing people? The Fire Department has been searching through the rubble. None of the bodies have been found.

---

Credits

Comments