My name is Samuel Singer, and I only have one ear.

I’ve written before about how I lost it in a previous article—it’s a mysterious tale of intrigue, mystery, and religious mania—but that isn’t what has brought my pen to paper today. How I lost my ear, however strange the circumstances, isn’t important right now.

What’s important is how it came back.

It happened quite literally overnight. It had been months with the ear gone, and I had gotten used to the way the world sounded, only using one earbud at a time, and the strange smoothness of my head against a pillow. I actually preferred to lay on the earless side. It was pretty comfortable.

Usually, it takes me a bit to fall asleep. I’ve seen some…things during my time as a journalist for my local newspaper, the Habitsville Gazette—things that like to make a reappearance in my memory when I close my eyes at night. But that particular evening, I felt different. Peaceful. And so, when I got in bed and laid down, flat side against my pillow, I fell quickly and blissfully into slumber’s soft embrace.

And then, I woke up screaming.

It was a terrible pain in my head that radiated down my neck and shoulders– a horrendous feeling, the brutal splitting of tender skin. I sat up in bed and brought my fingers to the side of my face. When they came back scarlet and sticky, I ran to my bathroom mirror.

My eyes were watering and blurry, and my fingers gripped the bathroom sink with tight knuckles. What I saw in the mirror was a horror film I could only watch out of the corner of my eye.

A wound had opened in the side of my head, two flaps of skin pushed aside by a flesh-colored nub. It was burrowing its way out like a baby bird from its shell, and the pain wrenched another cry from my throat. As I shouted out and watched, the nub forced its way out from somewhere beneath my skin, wriggling and clawing– then, as the tension finally broke, the nub unfolded.

And there, fused to my skull as though it had never left, was an ear.

I stared at it in shock. It was bloodied from its birth and looked odd in a place I was so used to seeing only flat flesh. But the pain was gone, and there was no doubt about it. That was my ear.

I rinsed the blood off and took a closer look. Once I got past the initial shock, I really should have been grateful. Not many people who lose an appendage wake up with it magically returned.

And yet, everything about this felt wrong.

The first issue—of which there would be many—was obvious from the start.

This ear, unlike my last one, couldn’t hear.

It didn’t pick up my last few anguished whimpers, nor the splash of the water as I cleaned the wound it made. It just sat on the side of my head like a prop, making my silhouette more balanced, but not much more than that.

But as I stood in front of the sink, heart beating fast, staring at myself in the mirror, I came to realize something. This new ear couldn’t hear, but it wasn’t completely silent, either. I had spent quite a while with no ear at all on that side of my head, so I was used to the feeling of dead, dull silence. But now, there was something there—some sort of white noise in the background, like when your television goes to static. I strained to make something out of it, or if the ear would start to hear normally after it adjusted to being on my head—but neither happened.

It took a few weeks for the novelty of my homegrown ear to wear off. After the initial shock and alarm, most people settled on the assumption that I had pulled some elaborate prank, although I don’t have a reputation as much of a trickster. I went to the doctor a few different times, was put on countless waitlists for specialists, but in the end, none of them believed the ear’s origin story, and none of them could get it to hear. Eventually, my dummy ear became nothing more than a party anecdote that no one would believe. And after even more time passed, even I began to forget about its strange origin story.

Until it switched on.

It happened while I was sitting on a bench.

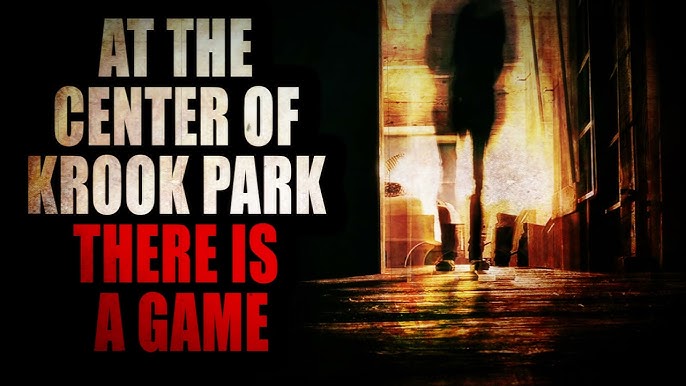

I had soured on my usual haunt, the Sage Diner, so I elected instead to try writing my next Habitsville Gazette article somewhere new, somewhere I wouldn’t be disturbed—The Alan Krook Memorial Nature Center—or, as us home towners call it, Krook Park.

I had been working on a piece that was actually interesting—a few local young men had gone missing: Parker Hewitt, James Seymour, Greg Clark, and Tommy Ross. They were upper-middle class, respectable, and the case had been the talk of the town since the second guy, James Seymour had gone missing a few weeks ago. He had been a Habitsville High legend, captain of the football team, baseball team, the whole cliché. And now he was just gone. And while that sucks for James, it’s great for a journalist.

But there hadn’t been any new developments since the last one went missing, and I was having trouble figuring out just how much more I could milk out of this small-town scandal. So, I did what I usually do when I have writer’s block. Look around aimlessly until a story comes to me.

A neighborhood park might sound quaint, but Krook Park isn’t. There’s no rampant crime or shady characters lurking. It just has sort of an eerie vibe—a fog that tends to collect low in the thicket of trees, and an empty playground that kids are never taken to, and teenagers never make out on at night. Even dogs steer their owners away from the park’s damp path. Needless to say, Krook Park is always empty.

Which is how I knew the sound my new ear picked up was coming from somewhere else.

It started as a few blips in the static I had grown used to—it could have been chalked up to a bit of ear wax—but then something cut through that couldn’t be explained away.

“Th—is –it folks, the---op of the----eighth--!”

The crackling voice made me jump, my pen falling away from my notebook and onto the ground. I looked around for the source, some sort of forgotten radio or pick-up sports game—but I still seemed to be completely and utterly alone.

Then, a sound like the ocean came through, cutting in and out—and I realized I was hearing the boisterous cheering of some distant crowd.

“That’s—trike one------ strike---oo-- !”

The buzzing of the crowd grew louder inside my head. Then the announcer exclaimed, “STRIKE THREE!” and the crowd went wild.

It was a curious thing-- I was alone on the bench, alone in the park, so I didn't feel odd about experimenting. If I turned my head a certain way, the sound seemed to come through a bit better. In fact, when I held my ear facing towards the thicker portion of trees in Krook park, the crackles lessened, and I could hear the announcer call the next batter.

"And next up to the plate, James Seymour"

I sat frozen. That name was familiar, mostly because I had just finished scribbling some notes about that very person, along with a few others: James Seymour, Greg Clark, Tommy Ross-- the young Habitsville men who had been reported missing.

It had to be a fluke, simply a case of two people with the same name. But, was it possible... the missing boys were all out playing baseball?

I kept my head cocked at an angle, grabbed my pen and notebook, and stood up. And, looking like a person with a terrible neck injury, I began walking, stutter-step, towards the thicket of the woods.

I changed direction every so often, as the frequency floated into my new ear with newfound strength. I didn't bother to entertain how bizarre the situation was, how strange that I would listen to the demands of an appendage that abruptly grew on the side of my head.

I just kept walking.

Eventually, as I weaved between darkened trunks and over gnarled roots, the sound changed. It wasn't just the staticy sound of a radio-- now, overlapping with just the slightest delay, I could hear the sounds of the game with my other ear. I was getting close.

I could smell popcorn and hot dogs and stale beer, and soon I could spy a break in the tree line. I had to be a few miles towards the heart of Krook Park, farther than I or anyone I knew in Habitsville had ever gone.

And yet, when I broke through the trees, I found a set of bleachers, packed to the brim.

I recognized a few of them, older men from the rotary club, my new mail carrier-- there were a few families there as well, the parents chatting together, the children sticky with red candy apples.

It was odd enough to make me want to stay undercover, and I moved just along the tree line, careful to stay out of sight. I moved until I was between two sets of bleachers, with a gap between that I could peer through.

It took a split second for my mind to catch up with my eyes, but when it did, a deep shudder of dread ripped through me.

The men were so severely bruised, bloodied, and emaciated they were almost inhuman. They wore uniforms in tatters and covered in dark stains, as though they had been wearing the same pants and jersey for weeks. The skin that shone through were lacerated with open wounds, dark purple and blue hematomas, or blazing red and blistered from severe sun burns.

And then there was a sound-- not over the radio my new ear was still picking up, but one that was traveling through the air in the moment. Though I don't consider myself much of an athlete, I did play a bit of baseball in middle school, and the most satisfying bit of an otherwise traumatic ordeal for a scrawny kid was the sound the bat made when it finally connected with the ball. If it was a metal bat, it would make a sharp ding, or a wooden one would make a nice vintage crack.

And yet, the sound I heard coming from where home plate was, on the baseball field in the center of Krook Park, can only be described as a dull thud.

Even from my distance, I began to smell it. The acrid stench of fear, pain, and despair wafted through the holes in the chain link fence towards me. And as I watched, my feet rooted into the sand-speckled dirt, the next batter stepped up to the plate.

Ba--ba-tt-tt-ee-rr--u-up-p-!" I was still hearing the announcer both on a delay and, unfortunately, in reality, and the echoing effect was causing my head to ache and my stomach to turn. I could see a man stagger up to home, where another man squatted behind the plate. I couldn't see their faces as they turned towards the rest of the field, but there was something so defeated about the way they moved, like beaten dogs.

They waited there, and the crowd's chatter quieted as they waited for the pitch. But, something wasn't right. Well, many things weren't right, but there was one in particular that I hadn't spotted at first. But once I did, it heightened my confusion even farther.

There was no equipment.

This wasn't just some negligent pick up game where the guys didn't wear helmets. There were no gloves on any of the players hands, and the batter stood at the plate, knees bent, but there was no bat raised over his shoulder. It was bizarre, like watching a courtroom reenactment of a baseball game.

And then, the player on the worn down mound threw the first pitch.

thud.

The ball went surprisingly far—at least, for an object hit by the forceful swing of a human arm.

The man who had swung didn’t cry out, didn’t so much as whimper—he just began to run. His welted arms pumped as fast as they could, but his legs staggered and swayed down the chalk line. The other players scrambled for the ball, dust flying up and into their noses and throats, but they chased after the ball as they choked in the haze.

Finally, the second baseman got the baseball in his grip, and as he straightened up, he hurled it towards the first baseman, who unbelievably, caught it in his bare hands with the sharp crack of already broken finger bones fracturing even more.

The batter’s foot hit the bag just after the baseman caught the ball. The running man collapsed in the dirt, making a terrible strangled noise of pain amidst the dust. The other players stared at the ground, unmoving, as the crowd’s cheers roared unsynchronized between my two ears.

Then, as the screams faded, there was a sound—some sort of scraping against asphalt. As it reverberated against the trunks of the surrounding trees, the spectators went completely silent.

As I watched, a huge bucket was dragged out of the home field dugout by the third baseman. With a resigned push, he tipped it over, and out spilled about thirty baseballs that rolled in a wave across the field. They hit the shoes of the players, and some picked them up immediately, while others stared a long time at the spheres before painfully bending over and grasping them.

As a solemn group, they shuffled over to the batter, who had sat up in the dirt, but had been too weak to stand.

“No…”

His voice came out in a raspy whimper.

The men circled around, their faces long and shadowed. Then, one by one, they raised their arms.

“N-no, p—p-leas-se-!” the man’s agonized scream echoed in my head.

The cry continued after the first nine balls pummeled into his soft flesh—but one particularly hard crunch to his head, and the rest of the throws fell quiet and dull.

Eventually, the last ball was thrown, and all the white leather was stained red.

Then, the announcer’s voice resounded across my ears.

“H-E-E’S O-O-U-U-T-T-T-!-!-!”

The crowd went wild.

I began to run.

The insatiable need to escape overpowered me as my feet found the ground and I dove into the thick wall of trees, hoping it was the way I had arrived. I could still hear the demented cheers in my head as I weaved between mossy trunks.

“Th—a—t’s the b-all gam-e fo—olk-ss-!” I heard on only one side as I traveled farther and farther away from the bloodshed I had witnessed. And then, just as I broke through the wall of trees, back into that blissfully misleading section of ordinary park, it went silent.

The game was over, and my ear switched off.

I haven’t heard anything from it since, and though I tried to let authorities know about the missing young men in the center of the woods, it was no use. Most of them thought I was insane. A nice deputy offered to take me to the local shelter.

Though I haven’t gone back to look for myself, I heard that the few officers that actually went to the center of Krook Park only found a wide clearing in the center of the forest, covered with fresh, moist dirt.

Comments