Do you know what happens when you burn a live body?

The process takes longer than you think. It will continue to burn, feeding on itself, like a nub of wick on a candlestick. After a while, the body's natural defense mechanism starts to kick in. At the site of incineration, all blood and fluid delivery is shut off, attempting to limit the pain. But, there is nowhere for all of those materials to go, so they leave the body, a great leaking faucet onto the ground, the carpet, the wood of the stage.

The palm of your hand makes up about one percent of your entire body. This process, the expunging of fluids, begins when more than a quarter of the body is burned. Back in the days of witch trials, it would often take a few hours before the person finally died.

It took me one Google search to learn all of that. I would only guess that Emma Livry knows it too.

I’ve tried to figure out who could have left me the note, along with my Act Two ticket, but so far, I haven’t come to any concrete conclusions. However, after doing extensive research, the day of the second performance, I have some new information. And maybe, one potential lead.

Looking with fresh eyes, after witnessing the atrocities that had taken place on the stage the previous night, I unfortunately understood more than I had before about Madame Taglioni’s Ballet’s website.

For one, those date ranges I saw under each Farfalla’s headshot—I now knew what they were.

Birth and Death.

The majority stopped at around ages 17-21, the same ages as most of the Ballet’s dancers. Franziska Wilde was there, her picture taken before her disfigurement, the second year after her birth left blank.

Whatever happens in Act II, it almost always kills Farfalla. Which meant it would probably kill Emma too.

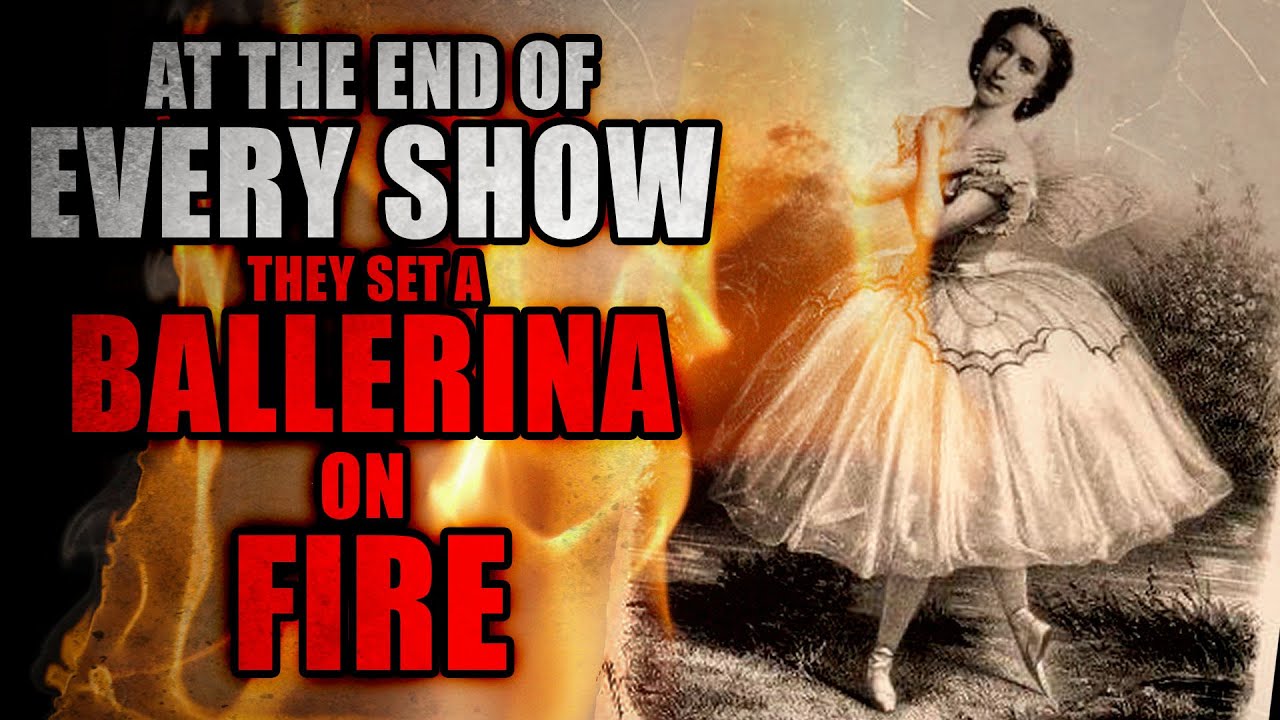

Another thing I’ve learned, which I’m sure many of you have already deduced, is what exactly happens to Farfalla at the end of the play.

To put it simply, she’s set on fire.

Farfalla, still stuck in her butterfly form, is attracted to the bright glow of a torch. As she dances nearer and nearer, her wings catch fire, and as she leaps and spins across the floor, she sheds her butterfly form, and is turned back into a young woman.

Or, in this case, she sheds her human skin, and turns into a corpse.

I was getting more and more anxious. Time was slipping away too quickly, and I had no idea what I was going to do. It was afternoon at that point, Act Two, Emma’s death, all only a few hours away.

Whoever left me my tickets, most likely both the first and second time, was someone who wanted me to stop this. I didn’t know why they had chosen me, or what exactly they had in mind as to what I should do. It seemed impossible, to stand against something that everyone, Madame Taglioni, the dancers, the audience, all of them seemed to be on board with. I felt alone, like I was the only one who could see the situation for what it was.

But then, I found her.

As it turns out, I’m not the first reporter to look into Madame Taglioni’s Ballet. There was someone else, a woman, named Mathilde Reid. She wrote for a paper in Augustus in the 90’s, one that’s since been shut down, which is probably why I couldn’t find her in my preliminary search.

In July of 1999, she wrote an article about Le Papillon. The paper doesn’t have a website, but it looked like someone had archived a photocopy on a amateur site about Augustus history. The headline read:

Madame Taglioni’s Mystery Ballet—Not What It Seems?

Disappointedly, the article didn’t really go into anything new. It mostly speculated about things I already knew to be true—the hidden location of the performance, the violent nature of the dance, etc.

But the article’s contents hadn’t been what caught my attention.

Instead, it was the author’s headshot at the bottom.

I had seen her before.

I went back and checked to be sure. Although her last name had been changed, from Reid to Robertson, there was Mathilde.

The 32nd Farfalla of Madame Taglioni’s Ballet.

I immediately started calling every number I could find, ballet studios, news outlets, anything in the area that might lead me to her. But, no one had any information. She didn’t seem to be anywhere in Augustus. I found a few more of her articles from the late 90's, most of which were about ballet and dance. She was an accomplished dancer, which I suppose she would have to be, in order to make Farfalla. But her articles tended to attempt to expose the darker sides of the sport—abusive practice techniques, instructors that withheld food, dancers suffering injuries due to an unsafe performance environment.

I couldn’t find a direct number or address, although I knew she was alive, since the second spot in her year bracket on the Ballet’s website was empty. She was Farfalla in 2002, three years after she had written the article about Le Papillon. Was it possible she had gone undercover? Or had she gotten sucked into the very madness she had wanted to expose?

But then, I remembered something.

“You know, in their 32nd year, they only made it part of the way through Act One because Prince Djalma’s crown got caught in Farfalla’s wing and ripped the whole thing off.”

The girl with the goldfish ring had told me that off-handedly, but it could be the key to everything.

Unlike Mathilde, the 32nd Prince Djalma wasn’t nearly as difficult to find. His name is James Arden, and he works as a dance instructor in Oregon. Like after being in Madame Taglioni’s Ballet, he had to get an entire country’s distance between them.

I could feel my heart beat in my ears as I dialed the number from the website.

A click. “Arden Ballet Instruction, how may I help you?”

“Could I speak to James Arden?”

A pause. “Speaking.”

I swallowed hard. “Hello Mr. Arden, this is Samuel Singer.” I waited, in case there was any sort of recognition there, something to suggest he’s had anything to do with what’s been happening. There was nothing.

“Good morning Mr. Singer. Would you like to make an appointment?”

“No,” I said. Then, after a deep breath, “I wanted to speak to you about Le Papillon.”

I was surprised when James sighed. “Look, I’m getting tired of these calls. I have no connection with Taglioni anymore, I can’t get you an audition spot, I’m sorry—“

I tried to interrupt. "No, that's not--"

He pushed on. "There are plenty of good ballets. You kids don't need to get yourselves involved in--"

“I wanted to talk about Mathilde.”

There was quiet on the other line. A few pulses passed as we both breathed into the receiver.

“Mathilde Robertson? She was Farfalla in our show. Very talented.” He was curt, and spoke as though he was thinking carefully about each word he said.

“No, not Mathilde Robertson,” I said, equally as carefully. “Mathilde Reid.”

There was absolute silence.

“Are you still there?” I asked.

“Who did you say you were again?”

“Sam Singer,” I said quickly. “Look, I just want to know where I can find her. It’s important.”

I could hear him hesitating, not trusting me. “I’m sorry, I don’t know where she is.” He paused. “I wouldn’t get involved with her, though. If you know what’s good for you.”

This piqued my interest. “Oh? Why not?”

He paused. “She convinced me to ruin the biggest performance of my life.” Then, before I could say anything else, he spoke again. “Look, this was twenty years ago. I don’t want to rehash it. Good luck with whatever it is you’re trying to do—“

“Wait,” I said suddenly, betraying the urgency in my voice. “Please. Someone’s in danger, and I think Mathilde might be the only one who could help.” I had no idea if that was true, but it was my best lead yet, and I was running out of time.

He waited a long moment, so long I thought he might have hung up, until he let out another heavy sigh.

“She's got a kid. A boy. I think he still lives in the city. Ask him.”

Click

---

Credits

No comments:

Post a Comment